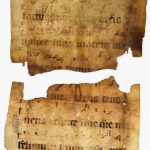

Further fragments from the same codex: (1) Budapest, Hungarian National Archives, pallium of F 15 Protocollum No. I. [1629–1638]; (2–3) Cluj-Napoca, Biblioteca Academiei Române – Filiala Cluj-Napoca, Old Hungarian Book Collection, covers of C 218, C 55090; (4) Budapest, Library and Information Centre of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Department of Manuscripts and Rare Books, T 422/6 (in our system: F 34).

The fragment was restored in 2022 by Veronika Szalai on behalf of the Momentum Digital Music Fragmentology Research Group, with the kind permission of Antal Babus, Head of the Department of Manuscripts and Rare Books of the Library and Information Centre of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

Before restoration, the fragment has served as the cover of a binding board without a book itself. After restoration, it was possible to identify the carrier: an 18th-century manuscript by Dániel Cornides (1732–1787) on Dacia. However, as Fanni Hende pointed out, the manuscript could not have been the original carrier of the fragment. This is contradicted not only by the late date of the manuscript’s creation and the late age of the binding (18th century), but also by the difference in size between the manuscript and the bookboard. It is therefore probable that at an earlier date, the manuscript was used as the cover of an unknown book, and that the entire binding was removed and placed on a second manuscript, that of Dániel Cornides. The identification of the valuable maculature material recovered during the restoration and the reconstruction of the background history of the carrier books was carried out by Fanni Hende, who published the results of her research in her study “What do the host books bound in the leaves of the Transylvanian Antiphoner reveal?” (see Bibliography).

The two surviving leaves contain a part of the Palm Sunday Office. The recto, revealed during the restoration, has a Deus Deus meus beginning with a cadel of a human head to aid identification. It is preceded by a pale red V letter (abbreviation of Versus) belonging to a responsory. In Western liturgical uses, this verse was part of the responsory beginning Deus Israel propter te on Palm Sunday. Although the beginning of the chant is missing here, the continuation makes it clear that this is the one in question. The chant ends on the verso, followed by the usual repetenda (Quoniam), and then a new responsory with a blue I lombarda beginning, Ingrediente Domino. At the bottom of the folio is the verse of the second responsory: Cumque audisset quia.

Thus, only two chants, two responsories, can be identified, but even this small amount of content is informative. The two responsories are only in the Esztergom diocesan tradition situated as the last two chants of the Matins – see László Dobszay–Andrea Kovács, Corpus Antiphonalium Officii – Ecclesiarum Centralis Europae. V/A Esztergom (Temporale), Budapest: Institute for Musicology, 2004, 158, in contrast to the Kalocsa-Zagreb and Transylvania-Várad assignation, which differ from this order (Andrea Kovács, Corpus Antiphonalium Officii – Ecclesiarum Centralis Europae. VI/A Kalocsa–Zagreb (Temporale). Budapest: Institute for Musicology, 2006, 89; VII/A Transylvania–Varadinum (Temporale). Budapest: Institute for Musicoloy, 2010). An examination of the liturgical content and selection of chants leads to a confusing conclusion based on the above. In the structurally more flexible parts of the chant, where there was more room for variation, such as the responsories of the Matins, the fragment did not present the versions of the Transylvanian–Várad breviary, but rather the Esztergom ordering.

We cannot form a picture without comparing the melodies. Our analysis of the five fragments that belong together confirmed the results of the liturgical analysis: the musical formulas are closest to the mainstream of Esztergom (see László Dobszay – Janka Szendrei ed., Responsories 1–2. Budapest: Balassi Kiadó, 2013). However, an important addition must be made here. For the one or two tonal differences that do emerge in comparison to Esztergom, the fragments keep with the renowned Anjou-period manuscript, the „Istanbul” Antiphonal (Studies and facsimile edition in Mária Czigler – László Dobszay – Janka Szendrei – Tünde Wehli, The Istanbul Antiphonal, about 1360. Facsimile edition and studies. Budapest, Akadémiai Kiadó, 1999), i.e. the melodies of the fragments are the closest relatives of the versions of the Istanbul Antiphonal.

Our final question is, can the Kolozsvár/Cluj provenance of the codex fragments be supported by the Cluj origin of the preserved host volumes? Unfortunately, very little and uncertain data are available to answer this question. The previously assumed Benedictine provenance of the leaf and its four sister fragments in the collections of Budapest and Cluj can be ruled out based on the liturgical content: the three Nocturnes of the Matins indicate a secular ecclesiastical use. Some of the sites in Cluj are excluded because of the presumed foreign colour of the liturgical customs there: for example, the Church of St Michael in Cluj was visited by a German-speaking congregation in the Middle Ages, which may have used service books written with different, Messine–German Gothic notation, with a different chant order, following the practice of the Transylvanian Saxon churches. (Although the Transylvanian Saxon cities of Sibiu, Brasov, Mediaș, etc. were directly subordinated to Esztergom, the content of their liturgical codices is not related to the Hungarian but to the German tradition). The use of St. Peter’s Church as suggested by Fanni Hende is worth considering, since this church in Cluj was the place of the Hungarians. But Hende also points out that from 1414 the parish priest of St Michael’s took over the liturgical service in St. Peter’s Church, and as a result, we can assume that there were foreign, Saxon-type liturgical books as well. Thus, it may not be a liturgical manuscript from Cluj, but from another Transylvanian church. The data currently available do not allow us to reach a more precise conclusion.

Gabriella Gilányi