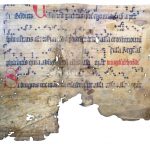

The fragment was removed from its host volume in December 2019, in the restoration workshop of the Archdiocesan Archives of Alba Iulia (Gyulafehérvár) at Șumuleu Ciuc (Csíksomlyó) with the participation of chief archivist Rita Magdolna Bernád (Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Alba Iulia). Restored by Árpád Benedek.

Notes on liturgical and musical content

The fragment preserved parts of the office of Saturday and Sunday after Ascensio Domini, as well as the Vigil of Pentecost.

The outer side, which served as the cover of the host book, was much more exposed to adversity than the inner side, making the reconstruction of the transmitted chants extremely difficult. This external side was the recto of the original folio, which presumably maintained two responsories of the Saturday Matins (Non turbetur with the vers Nisi ego abiero, previously written down in the Matins of the Ascension Day, and therefore prescribed here only in an abbreviated form), the fully notated R. Exaltare Domine + V. Cantabimus et psallemus, and the Benedictus antiphon Dominus quidem Iesus of the Lauds.

In addition to the rubricated invitatory, texts and melodies of three antiphons can be reconstructed on the verso, two of them almost completely. The canticle antiphons sung in the Lauds and Vespers on weekdays presumably followed one another as a cycle in the original manuscript; we find this way of arranging the chants in most of the late medieval office sources, including the Hungarians. The (allelui)a, which can be spelled out at the beginning of the first line of the verse with the initial word of the Benedictus canticle are remnants of the closing chant (Benedictus antiphon) of the Lauds on Sunday after Ascensio. Both the end of the word alleluia and the last notes (gag) of the psalm differentia above Benedictus suggest that this is a torso of the antiphon Dum (or Cum) venerit Paraclitus quem ego mittam vobis, spiritum veritatis, qui a Patre procedit, ille testimonium perhibebit de me, alleluia in mode 8 (Janka Szendrei–László Dobszay et al., Monumenta Monodica Medii Aevi V. Antiphonen. Kassel–Basel: Bärenreiter, 1999), 8400; online: http://melodiarium.zti.hu/cantus-officii/antiphonae/). After the chant that can be reconstructed on the basis of one word and only a few notes, the Magnificat antiphon (Cum venerit Paraclitus, quem ego mittam vobis a Patre, spiritum veritatis, ille testimonium perhibebit de me alleluia, et vos testimonium perhibebitis, quia ab initio mecum estis, alleluia) of the second Vespers on Sunday after Ascension Day follows. Among several antiphons with similar text incipit of the Pentecostal chant series, with its symmetrical-articulated structure, this mode 1 Cum venerit might be considered as one of the newer compositions-compilations of plainchant. Its sources come almost exclusively from the Central European territory. At the level of microvariants, the melody in the fragment corresponds to the melodies found in the central Hungarian antiphoners (cf. Monumenta Monodica Medii Aevi V. Antiphonen, 1440; online: http://melodiarium.zti.hu/cantus-officii/antiphonae/).

In the last line of the verse, a rubric introduces the office of Pentecost’s Vigil. The rubricated Alleluia. Regem ascendentem is certainly the invitatory antiphon, followed by the Magnificat antiphon of the Vespers Si diligitis me mandata, fully notated. The latter is a common piece of the Western chant repertory, which was found as a Gospel antiphon of the week of Pentecost and (especially in the early monastic and Franciscan sources) in the office of the apostles Philip and James. We find a difference in its modal interpretation: apart from the smaller variants, depending on the transposition of the closing alleluia, the same melody is assigned to mode 8, closed to g by some sources, while others (including our fragment) interpret the melody in mode 3 with a closure on e. (cf. http://www.cantusindex.org/id/004886).

If we can believe the data of the Cantusindex, it was more common to interpret the antiphon in mode 8 – as defined by most Western and Central European sources. However, the codices representing the Franciscan tradition, including the Franciscan Antiphoner of the Budapest University Library (OFM-122) and the sources coming from France, contain predominantly the mode 3 version. Of the representative diocesan sources in medieval Hungary, it occurs only in the Istanbul Antiphoner, in line with our fragment, also as mode 3 form (see the melodies in the online music database of Hungarian office anthiphons: http://antifona.zti.hu/). Considering the antiphons’s sources in Hungary, the Gheorgheni fragment is of particular importance and fills a gap. We cannot rule out, although additional source data are needed to prove this, that a traditional feature of a narrower liturgical version represented by the original antiphon survives in it.

Notes on notation

On four thinly drawn red lines, black notes can be read in 4 staves; there is no frame. The top staff is truncated due to the excision of the leaf, the upper side is missing. Unfortunately, it is not clear how many staves may have been on the original codex folio. The c and f-clefs are shown at the beginning of the staves. A special hair line running from the elongated upper element of the c-clef is unique, the multiple appearance of it precludes randomness. Only in the Graduale from Gheorgheni we saw the same rare drawing of c-clef – a little running stroke – from which we can deduce the very close kinship of the notation of the two sources (see also the analogies of clivis and pes structures).

The leaf was notated in Gothic style, i.e. some elements of the neumes were thickened and enlarged. The effect of the mixed Messine German Gothic notation can also be shown in the articulation of its neumes. In 15th-century Central European Gregorian manuscripts, this is the most common pen-handling technique: notes and neumes are arranged in regular geometric shapes by it. All of this made it easier to sing in the church: in the late Middle Ages, it was mostly no longer sung from memory but from codices: the choir book was kept on a stand during the ceremony, surrounding it by the choir. Similarly to the Gothic notation, the rhombus-shaped punctum in the fragment is the basic unit of writing, which is supplemented by line elements in certain neumes (pes, clivis, scandicus): these vertical stokes are separated from the notes, with the exception of the archaic 7-shaped clivis, i.e. the writing has an articulated structure.

The Gothic writing technique in Central Europe was mostly mixed with elements of the local plainchant traditions, thus becoming a system suitable for notation large codices, so that the mixed notations did not completely lose their original individual features. The neume system in the fragment is also such a mixture: in addition to the foreign, fashionable elements (rhombus-shaped note head, articulated pes), we can recognize the structures of early Hungarian / Esztergom writing, and even its eastern peripheral elements.

Earlier Messine/Esztergom neume is the already mentioned 7-shaped, mostly conjunct clivis variant, but at the same time this neume drawn with a long slanted upper part is a distinctive feature of Eastern Hungarian and Transylvanian notations. The special clivis form, which is actually divided into two puncta, can also be documented mainly from Eastern traditional schools and the Pauline Order. A similar variation can be observed in the case of the climacus: the characteristic feature of Esztergom is the form starting with double puncta, which is tilted to the right in the same way as the late Messine German mixed writings. At the same time, besides the beginning with double points, a vertical, simple starting version can also be discovered, which, together with the archaic vertical point-series of neume compositions, appears to be the dominant structure of the musical layout, proving that the above modern (right-hand) writing direction is only occasional in this notation. All this also indicates that the original choir book has not yet reached the size for which a notator would be forced to write the puncta-series obliquely. A characteristic sign of Esztergom is the scandicus shown here (it has survived in the fragment only in neume-structure), which has therefore no longer a conjunct, but a new fragmented shape, and in which the second element (a stroke instead of punctum) still reminds us of the old Esztergom conjunct scandicus, i.e. the neume in the fragment is not composed in the Gothic punctum-punctum-virga form. The most modern feature of the writing is the articulated pes, which is no longer the inverted s-shape, but the punctum + virga composition divided clearly into two parts. Though the articulation is very definite, the second element is an individual, hook-shaped form (showing an influence of cursive notation), not rigidly angular.

Further elements can be discovered in the notation, which also refer to the Transylvanian origin. The custos is a variant of the so-called ‛Upper Hungarian’ guarding sign, in a special form, to which we have only seen analogies in Transylvanian sources: e.g. the custos of the Cantionale of Csíksomlyó is close to this form. In the latter source, a similar arrangement of the musical content can be seen, i.e. a specific alternation of the denser and airy sections acoording to the number of notes in a musical phrase, together with the analogies of the articulation in neume structures, they may be guides in determining the provenance. The similarly fine and thin ‛bar lines’ (kind of articulation strokes) of the fragment also appear in the above-mentioned Transylvanian sources.

In our opinion, the place of origin and destination of the ‛Gheorgheni fragment’ could not have fallen very far from its current keeping place. Analogies in the notation also suggest that its provenance can be traced to Southern Transylvania, in Székelyland.

Rita Magdolna Bernád, Zsuzsa Czagány, Gabriella Gilányi