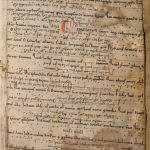

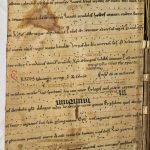

The description of the two 12th-century notated fragments in the 15th-century schoolbook (“Codex Demetrii de Lasko”) was expertly prepared by the Hungarian literary historian and codicologist Béla Holl in 1984. He noticed that the fragments had been fastened to a strip of leather as beginning and ending flyleaves between the boards and the spine, and then cut to the same size as the leaves of the manuscript. The contents are shown in the reverse position in relation to the main text. According to Holl, the binder may have intended to glue these parchment leaves to the inside of the book boards to hide the strips used for the binding and at the same time to reinforce the binding. For some reason, however, this was not done: there is no trace of glue on the fragments. Holl does not mention that the binders reinforced the quires of the codex with strips of parchment from a leaf of the same 12th century musical manuscript, perhaps to facilitate the binding of the quires to the leather strip. In addition to the first and last smaller quires, the book consisted of eight and seven units of bifolia, 18 in all. The 18 parchment strips also meet at the junction of the quires, i.e. they are doubled, are clearly visible when turning the leaves of the host book, with visible script elements.

The former mother codex was a mixed troper-proser: notated sequences attributed to Notker and a trope can be identified on the leaves. The first fragment contains Easter pieces, excerpts from the sequences “Laudes Christo redempti”, “Pangamus creatori”, “Agni paschalis esu”, “Grates salvatori” and “Haec est sancta”, the second preserved sequences for Christmas “Grates nunc omnes”, “Natus ante saecula” and “Eia recolamus”, as well as the rare but not unknown Christmas troped (farsed) lesson “Laudem Deo dicam”, which was not unknown in medieval Hungary: two occurrences were documented earlier (see Janka Szendrei, Fragment T 256 in the Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. The significance of two occurrences of “Laudem Deo” in Hungary, in Melinda Berlász-Mária Domokos ed., Studia Musicologica. Budapest: HAS Institute for Musicology, 1978, 19–34). Laudem Deo has musical parallels in Western sources, and is one of the best known of the so-called farsed lessons. The music of the farsa is cento-like, including parts of pre-existent sequence melodies. (cf. David Hiley, Farsed Lessons, Creeds and Paternoster, chapter xii in Western Plainchant. A Handbook, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993, II. 23, 233–238) After the beginning of Laudem Deo dicam, the trope insertions divide the text of the reading into short sentences, following one another in a dense sequence, as can be seen in the excerpt from the Šibenik troper-proser, where the trope text is given in smaller letters, further separating its lines from the reading text. The larger size of the reading text explains the significant difference in the layout of the two fragments, which is why the Laudem Deo-leaf has only 11 lines with text and music instead of 14.

In terms of its melody, the Laudem Deo legible on the fragment is very close to the variant of the Missale Notatum Strigoniense (f. 367r, http://cantus.sk/image/17580), in addition, a fragment from the Graduale Varadinense (see F 025) provides a significantly different polyphonic organum technique. This confirms Szendrei’s suggestion that the Laudem of Esztergom represents a strikingly archaic version for its time. The MNS version was completed by the appendix semper o pie, whose form, alternating with vocalization or performed simultaneously with it, is unknown in the Western chant repertory. The Šibenik fragment also contains the semper o pie addition, alternating between the melisma and the melisma vocalization form. The two are indicative of the same ancestor, and perhaps even of a special domestic tradition, and evidence that Laudem Deo was certainly part of the Hungarian chant repertory from the appearance of the trope in the country.

A comparative study of the musical notation showed that the notable first layer of staff notation of the so called Codex Pray (a 12th-century sacramentary from Hungary) – which is traditionaly concieved as the earliest witness of the Esztergom notation – reveals a later stage of development of the Esztergom notation than that of the Šibenik fragment. Of the Šibenik and Kraków fragments [which also contain early Esztergom notation and was found in 2014 in the Jagellonian Library Kraków (Ms. 2372, see Zsuzsa Czagány, „Fragmentum Cracoviense Officii Sancti Demetrii Thessalonicensis”, Studia Musicologica 56/2, 2015, 173–188)], the notation of the troparium seems to be the more archaic. This supports the statement made by Szendrei in 1984: this manuscript is the first known example of the Esztergom notation. For a detailed musical palaeographical analysis see Gabriella Gilányi, “The Codex Demetrii de Lasko. Re-examining the two 12th century flyleaves”. Paper held at the conference of the “Momentum” Digital Music Fragmentology Research Group, 17. 11. 2021, Institute for Musicology, Bartók Hall.

Gabriella Gilányi