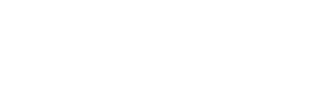

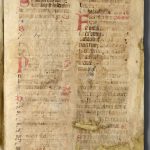

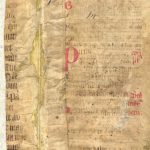

The Regestum, the book of accounts of the Castellan, István Pisky written as a paper-manuscript between 1585 and 1589 – now kept in the Archives of the Pannonhalma Archabbey – is a historical source of great value of the monastery of Tihany from its border-fortress-period of vicissitudes destitute of Benedictine monastic life. The manuscript containing the accounts of receipts and expenses registered by the castellan’s scriveners is covered with the bifolio of a missale notatum, i.e., a missal with musical notation. The content of this special mediaeval cover was earlier examined by László Erdélyi OSB, Kilián Szigeti OSB, Janka Szendrei and László Dobszay. Based on the history of the Regestum, Szigeti considered it to be of Benedictine origin from Tihany, but he did not research in depth its liturgical and musical content. Janka Szendrei did not deem the Benedictine origin properly verified, she considered its musical notation to belong to the tradition of Esztergom. In the light of the available mediaeval domestic and foreign liturgical sources and making use of the possibilities offered by the newer databases of the comparative history of liturgy and melodies, and those of research in musical palaeography, shed light to the forgotten history of the binding of Pisky’s book of accounts.

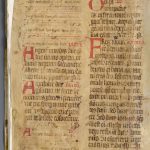

The first folio of the mentioned noted missale contains a short section of the liturgical commemoration of Pope Silvester (31 Dec) and the most of the material for the Sunday celebrated in the Octave of Nativity. The second folio reveals the material for the second Sunday after Epiphany from the Alleluia, and for the third Sunday, including the Introit, the Collect, and the beginning of the Epistle. The three tiny fragmentula used for the binding of the Regestum belong to the same leaf, all of them contains the material of Sexagesima Sunday.

The scrupulous analysis of the liturgical texts (readings and prayers) reveals many archaisms, which are unknown in Hungarian mediaeval sources. In this respect, an optional postcommunion (Auxiliare Domine populo tuo) recorded in second position for the second Sunday after Epiphany can be conclusive as for the fragment’s provenance: it was found only in two 11th-century Italian monastic sources (cf. https://digi.vatlib.it/view/MSS_Vat.lat.4770/30; https://digi.vatlib.it/view/MSS_Arch.Cap.S.Pietro.F.12).

The fragment’s musical notation is minutely examined, which is strictly speaking of the Esztergom-type and fits in well with its specimens known from the first half of the 14th century. The melodic analysis reveals three aspects: (1) we examine the dialect of the repertory, which is pentatonic in accordance with the diocesan customs of Central Europe; (2) we touch upon the chant settings, which can reflect the customs of a diocese independent of Esztergom; (3) and we search for characteristic melodic variants, which also indicate a tradition of this kind that cannot be exactly defined yet for the time being. Based on the writing of letters and the musical notation, the fragment’s age can be related to the first half of the 14th century.

Two layers can be separated in the liturgical content of the given missale notatum: an archaic text showing some monastic parallelism and a contemporary diocesan chant repertory. The codex once having included the fragment might even have been composed in a way that the scribe copied the items of his regional musical tradition and the text of an archaic sacramentary into the same volume. Since the monastic relationship of the textual source can firmly be rendered probable, it has a serious chance that the parchment cover of Pisky’s book of account is really of Benedictine origin and was truly copied in the scriptorium of Tihany. It is a realistic assumption that the monks leaving the monastery at the beginning of the 16th century left behind the outdated missale notatum, and one of the in-coming scriveners made the manuscript’s cover from the pages of this volume. If our train of thoughts is correct, the fragment in question verifies that at the beginning of the 14th century the Benedictines in Tihany used the same musical notation in the monastery as the scribes of the cathedrals, and their chants for mass were not substantially different either from the ones sung in cathedrals (at least at Christmastide and around Epiphany). Other fragments of noted liturgical manuscripts used by Benedictines in Hungary during the 14th century are unknown.

See the physical description and the detailed analysis of the binding of Pisky’s Regestum in the paper given in the Bibliography, available in the Bibliotheca.

Gábriel Szoliva