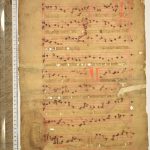

The fragment reveals a particularly beautiful Hungarian musical notation. Previous research (Mezey, Fragmenta Latina codicum, 188, see Bibliography) considered the fragment to be of Pauline origin, and, on the first sight, the conjunct structures of the notation seemes to confirm this opinion. However, based on an overview of the liturgical-musical content, doubts may arise. Though the fragment contains parts of the office of Saint Augustine, who was highly respected among the Paulines – antiphons of the first Vespers (the Laetare mater nostra cycle) and its responsory (Vulneraverat caritas) ‒, some of the antiphons are not associated with the characteristical Pauline melodies, but with the Esztergom version (see e.g. a5 Inventus igitur). It is noteworthy that some (melodically identical) chants, e.g. the responsory, at the level of musical microvariants diverge from both the Pauline and Esztergom versions, and resemble mostly to the melodies of the Várad (“Zalka”) Antiphonal. (Cf. Antiphonale Varadinense II, f. 77r–79r, facsimile edition: Zsuzsa Czagány, Antiphonale Varadinense s. XV, vol. II. Proprium de sanctis et Commune sanctorum, Musicalia Danubiana 26/2, Budapest: Research Centre for the Humanities, Institute of Musicology, 2019. More to the Hungarian variants of the Augustine-office see Janka Szendrei, „Középkori zsolozsma Szent Ágostonról” [Medieval historia for St. Augustine], Magyar Egyházzene 3, 1995/1996/1: 37–50).

The Pauline provenance is not clearly supported by the analysis of the musical notation either. It seems that the beautiful traditionalist notation can be registered from two late medieval peripheral notation schools: on the one hand, from Pauline and on the other hand, from Transylvanian diocesan environment. Examples of the former are: Zagreb, Nacionalna i sveučilišna knjižnica, R 3612 (15th–16th cover of an 18th century Pauline processional); Budapest, Central Seminary, Pauline Library, Fr. l. m. 90; Budapest, University Library, Fr. l. m. 255 (fragment F 796 in our database); Franciscan Library at Csíksomlyó/Şumuleu Ciuc (Romania), Sign. Inv. 744 (cf. Zsuzsa Czagány – Ágnes Papp – Erzsébet Muckenhaupt, „Liturgikus és kottás középkori kódextöredékek a csíksomlyói ferences kolostor egykori könyvtárának állományában” (Medieval liturgical and notated manuscript fragments in the former collection of the library of the Franciscan Convent at Csíksomlyó), in A Csíki Székely Múzeum Évkönyve (Annual of the Szekler Museum of Ciuc) 2005. Társadalom- és Humántudományok. Miercurea Ciuc, 2006, 149–232, Cz. Fr. 11, see in the Bibliotheca); Cantionale of Częstochowa (Częstochowa, Klasztor OO. Paulinów Jasna Góra, R. 583 /I-215, notations on p. 14 and 384). Fragments from the later notation school related to Transylvanian diocesan use can be: Budapest, Central Seminary, Pauline Library, Fr. l. m. 120; Library of the Franciscan Convent at Güssing/Austria, 4/184; Franciscan Library at Csíksomlyó/Şumuleu Ciuc (Romania), Fragm 53; ibid., Sign. Inv. 3786 (cf. Czagány – Papp – Muckenhaupt, Cz. Fr. 8); and assumedly the fragment in question.

The common feature of these notations is the distinction between the size of the punctum and other neumes: the punctum is enlarged compared to the other elements, they presumably used a different pen. In addition to this common writing method, the differences between the two notation groups are also striking: the Transylvanian neume combinations are uncommonly thin, the horizontal-broken drawings give a slightly disordered impression, the angles are sharper, and the f-key also differs from the Pauline examples. Perhaps the antecedent of this angular-broken Transylvanian writing could be the notation of the leaf F 337 of the Szendrei catalogue (Janka Szendrei, A magyar középkor hangjegyes forrásai / Notated sources from the Hungarian Middle Ages, Budapest, HAS, Institute for Musicology, 1981), a fragment coming from an Eastern-Hungarian diocesan circle. This “angular” group of Transylvanian notation can be contrasted with another group of an elegant, “flowery” type also from Transylvania (see Gabriella Gilányi, Mosaics of the plainchant tradition of Transylvania. Interpreting the 14th century antiphoner fragments at Güssing. Resonemus pariter, Studies in Medieval Music History 1., ed. Zsuzsa Czagány, Research Centre for the Humanities, Institute for Musicology, 2019). The angular notation type could not be connected with South-Transylvania (contrary to the “flowery” one), its provenance should rather be sought further North. The host book of our fragment also suggests Transylvanian origin: the notes of István Szamosközy, a Transylvanian historian, were bound in the fragment.

Gabriella Gilányi