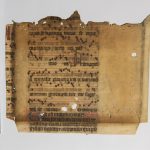

Three fragments of the Pauline Library of the Central Seminary (F 697, 698, 699) and a fragment of the University Library (F 813) come from the same codex, a 15th-century notated breviary from Bohemia. In two of the carrier books of the four related fragments (F 813, F 699) we find the ownership record of the Jesuit college in Pozsony (Bratislava) dated 1692. The carrier of F 813 contains also the name of another owner, Daniel Schmid. Schmid’s name appears also in the carrier book of the third fragment (F 698), which, however, does not contain the entry of the Pozsony Jesuits. However, we know about Daniel Schmid that he also worked in Pozsony as a Lutheran pastor from 1636, and several of his books bearing his name have been preserved in the collections of both the University and the Pauline Library (Fr. l. m. 106 in the University Library; Fr. l. m. 17, 79, 115 = F 845, 192 in the Pauline Library). Both the possessor entries and the common mother codex of the fragments serving as covers indicate that the books were bound in Pozsony, and that the bookbinder used for his work the parchment leaves of the Bohemian notated breviary. More on Daniel Schmid, see: Zsuzsa Czagány, “Music manuscript fragments with Bohemian notation in the Pauline Library of the Central Seminary in Budapest”, Magyar Egyházzene XXV (2021/2022) No. 1, 77–104; More to the carrier books owned by the Pozsony Jesuit college and the codex fragments surviving as their bindings, see: Edit Madas, „Beiträge zur Provenienz einer Fragmentengruppe der Bibliothek des Zentralseminars zu Budapest”, Ars Hungarica, 17 (1989), 47-50.

Two of the fragments (F 697 and 698) preserve parts from the historia of St Augustine Laetare mater nostra. The two fragments originally formed the upper and lower halves of a folio, now cut in half, with the 7th and 8th responsories of the Matins (Vulneraverat caritas, Accepta baptismi gratia). The fragments cannot be joined together completely. Based on the rectos’ responsory Vulneraverat caritas, which is divided into two parts, the gap between the halves might have been filled by two complete lines of text and music, plus the text of the chant at the bottom of F 697 and the line of notation belonging to the text that appears in parts at the top of F 698. Our calculation are also confirmed by the responsory Accepta baptismi gratia on the verso, which is cut in half: since the lesson preceding the movement is slightly shorter than the one on the recto, the almost complete first text and melody of the responsory are still on the upper half of the page.

On both sides of the two fragments of the breviary, which are arranged in two columns, the other edge of one column is visible in addition to the intact column, so that the other items of the historia can be identified from the remains of the notes and text at the end and the beginning of the lines. In this way, we can reconstruct almost the entire set of chants of the third Nocturn, and even identify the last responsory of the second Nocturn (Volebat enim) on the basis of the repetenda (In qua [alius]) and the subsequent parts of the doxology, which fortunately survive on the recto of F 697. The clearly visible rubric in the left column of F 697 recto – [i]n III [n]octurno an[tiphona] –helps us to orientate, and makes the liturgical placement of the chants written before and after it certain.

The fragment and the mother codex are undoubtedly of Bohemian origin. In addition to the typical Bohemian rhombic chant notation, this can be confirmed by a musical-liturgical argument. The historia of Augustine that survives on the two fragments was popular not only in Bohemia, but also in the wider Central European region from the 13th century onwards. Both the composition of the movements and their melodic setting were relatively uniformly spread. Within this unity, the more striking are the two different versions of the opening melodic formula of the responsory Accepta baptismi gratia, which are at one point sharply separated. The formula, almost everywhere, in a manner typical of the newer tetrardus mode compositions of the 11th and 12th centuries, first reinforces the G-final from below and then from upwards; in the latter, it extends the ambitus by moving in thirds to the fifth above the finalis before settling on the G (cf. Dobszay–Szendrei, Responsories II, 8186). In Bohemian sources, however, there is no ascent of a major key character of the ambitus, and the recitative melody moves in a narrower (third) interval above the word baptismi (see, among others, Antiphonale Kolín, Praha, Knihovna národního muzea XII A 21, f. 124r: http://www.manuscriptorium.com/apps/index.php?direct=record&pid=AIPDIG-NMP___XII_A_21____30TXYP6-cs; Antiphonale Hradec Králové, Muzeum východních Čech II A 3, f. 98v: http://www.manuscriptorium.com/apps/index.php?direct=record&pid=AIPDIG-MVCHK_HR_3_II_A_3_0JI5247-cs; Antiphonale OSB Praha/Monasterium St. Georgii, Praha, Národní knihovna České republiky XIV C 20: http://www.manuscriptorium.com/apps/index.php?direct=record&pid=AIPDIG-NKCR__XIV_C_20____2IMIY13-cs). The fragment, however, preserves this simpler melodic version, typical of Bohemian sources.

Zsuzsa Czagány

For the maculature (Latin and German prints) taken from the binding of the F 698 host book, cf. László Mezey, Fragmenta codicum in Bibliothecis Hungariae I/2. Fragmenta Latina Codicum in Bibliotheca Seminarii Cleri Hungariae Centralis, Budapest, Akadémiai Kiadó, 1989, 102.