For a description of the fragment’s former host volume in the online catalogue of the HAS Library (ALEPH) amongst Old Books – Rare Books (RBK):

The composite volume likely was bound in Kolozsvár (Cluj-Napoca in present-day Romania) in the bookbinding workshop of the Heltai-press: sheets of local prints from the years 1560–1570 were used as maculature of the binding.

Maculature: 1. (T 422/1) Antonio Bonfini: Historia inclyti Matthiae Hunnyadis. Kolozsvár, 1565. RMNY 209, 2 pieces; 2. (T 422/2) Heltai Gáspár: Disputatio in causa sacrosanctae et semper benedictae Trinitatis. Kolozsvár, 1568. RMNY 256, 13 pieces; 3. (T 422/3) Heltai Gáspár: Agenda, az az szentegyhazi chelekedetec, mellyeket követnec közenségesképpen a keresztyéni ministerec es lelkipásztoroc. [Agenda, namely acts in the holy church, which are commonly followed by the Christian ministers and pastors] Kolozsvár, 1559. RMNY 154, 2 pieces; 4. (T 422/4) 3 coherent strips from an assumedly 15th-century Eastern Hungarian gradual.

Further fragments from the same codex: (1) pallium of MNL OL F 15 Protocollum No. I. [1629–1638], (2–3) Biblioteca Academiei Române – Filiala Cluj-Napoca, Old Hungarian Book Collection, covers of C 218, C 55090; (4) Library and Information Centre of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Department of Manuscripts and Rare Books, T 261. For these see: Hende Fanni, „Egy erdélyi antifonále provenienciájának kérdései” [Questions on the provenance of a Transylvanian antiphoner], in „Mestereknek gyengyének” Ünnepi kötet Madas Edit hetvenedik születésnapjára. Ed. Hende Fanni, Kisdi Klára, Korondi Ágnes. Budapest, Országos Széchényi Könyvtár – Szent István Társulat, 2020, 79–91.

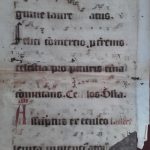

Parts of St. Vincent’s office are legible on the fragment. The repetenda in the Matin’s third nocturne refers to the responsory Christi miles used at this designation in Esztergom. The third responsory is Gloriosus Dei amicus, with the verse Felici commercio, they are followed by the first antiphon Assumptus ex eculeo of the Lauds according to the fragment. Although the Vincent office can be documented solely from the Várad breviary (I-Rvat 8247) belonging to the Eastern Hungarian tradition, it does not match with the chants seen on the fragment: there the last two responsories of the Matins are not Christi miles, but Agnosce o Vincenti followed by Gloriosus Dei athleta. Again, it is the Esztergom variant instead of the geographically closer Várad.

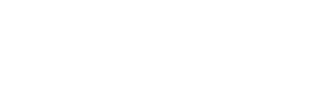

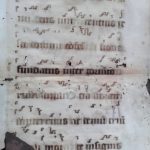

Janka Szendrei counted the notation of the fragments amongst the most peculiar Hungarian notations in her monograph on medieval notations, recognizing in their musical script both the characteristics of the 14th-century calligraphic Esztergom notation and the pen-technique pointing to a later emergence (the following conclusions apply to the entire group of fragments). Szendrei calls this traditional notation peripheral, with Transylvania as the most likely place of origin, while being adequately reserved concerning the designation (Szendrei Janka, Középkori hangjegyírások Magyarországon [Musical notations in Mediaeval Hungary], Műhelytanulmányok a magyar zenetörténethez 4, MTA Zenetudományi Intézet, Budapest, 1983, 73). The outcome of the detailed palaeographical examination is consistent with her proposal. The musical notation contains numerous curious, unique elements compared to the full-blown calligraphic central Hungarian notation: the appearance of the writing is airy and expanded, the notation almost disappears in the roomy staves despite its thick lines, although the growth of the notes/neumes in size is not parallel with the airiness of the staves. The scribe aims to precisely follow the conjunct Esztergom shapes with the thick lines, thus the notation is not ruled by dainty, thin lines, as at the turn of the 13-14th century in Esztergom, but by thick, rustic ligatures, which at the same time create a contrast with the thin lines of the staff. These together point to the influence of gothic pen cuts fashionable from the end of the 14th century, which is not yet dominant in the notation, as the scribe does not enlarge and part the neumes at this early stage (contrary to the scripts of the central Esztergom notation at this period, or a similarly peripheral notation, e.g. the neume structures in the 14th-century Transylvanian antiphoner kept in Güssing. See Gabriella Gilányi, Mosaics of the plainchant tradition of Transylvania. Interpreting the 14th-century antiphoner fragments at Güssing. Resonemus pariter 1. Studies in Medieval Music History, ed. Zsuzsa Czagány, Research Centre for the Humanities, Institute for Musicology, Budapest, 2019).

The basic syllabic sign on the fragment is the punctum, which has two forms: a regular rhombic form, and a note that – in most cases – is elongated to a rectangle. Therefore, there is not a standard punctum shape, while the form reminds of the angular basic neume of the Gothic notations of the era in Central Europe. The sign lays peculiarly aslope on and in between the staff lines: we can see the same in many sources assumed to be Eastern Hungarian and Transylvanian. Due to the special placing of the punctum, the slanted rectangular notes, which follow each other in the climacus or the combinations of the climacus, are connected on their sides, or rather they rotate around their intersection similarly to square notation. All the abovementioned are significant characteristics of the traditional peripheric planichant notation of the 15th century. Although the visual of the notation shows some parallels to the writing tradition of the central Hungarian notation, e.g. its traditional 15th-century thick and conjunct version used by the Pauline order (in their notation the traditional elements are also the thick, conjunct ligatures and the climacus starting with duble punctum), in the Pauline notation the standard rhombus slit by the staves are the characteristic basic signs, and their meeting at their points in all cases of vertical rows. The Pauline provenance of the fragment can be ruled out based on the above.

An important sign of provenance, and also an archaic trait in the fragment’s notation are the conjunct neumes, the emphasis on the ligatures, and on the vertical details of the neumes. The notation of the fragment is not the rounded, fluent form of the 13th-14th-century Esztergom sources, but it has its own characteristics, it is made of more angular, more linear, more robust elements, a subtype striving for individual stylisation (similar examples are fragments F 174, 337, 586 of Szendrei’s catalogue). It is possible to discover the roundedness and the contrasting play of the thin and thick lines in the shape of some neume’s initial line. The hair-thin initial lines make the notation “flowery”, this thickening-thinning of the lines in the punctum, clivis, climacus and porrectus is an important trait of the notation.

It is important to talk about some individual neumes. The upper part, the „hat” of the climacus is made of two connected, rudimentary puncta (the second one is more rough than the first). The following puncta under them meeting at their sides, hence leaning right are more regular and bigger in size – the “hatted” climacus is one of the main characteristics of the Transylvanian notation (see Janka Szendrei Középkori hangjegyírások Magyarországon [Mediaeval Music Notations in Hungary], 63).

The shape of the pes is also characteristic. It is not the flexible “s”-shape of Esztergom, but a sign reminding of a reversed “z”. Its shape is not rounded, but made of broken lines: this pes is also a variant representative of the eastern writing area of Mediaeval Hungary. The pes connecting a bigger interval, e.g. third is more archaic. The notes at the ends of the sign are not even full puncta: they connect more fluently to the dominant, thick linking line.

The scandicus is a fully conjunct form. Although the thick shape is broken by the scribe at the middle element, however, tries to keep the neume conjunct according to the archaic Hungarian notational tradition: this is not the end of the 14th-century scandicus disintegrating to its elements, as in the Güssing examples, it is more archaic.

The shape of the torculus is the union of a reversed “z”-shaped pes and a thick line: the scribe breaks the upper long connective element and draws a thick, distinct, vertical element to the end. This vertically ending torculus is another trait of Transylvanian fragments. The porrectus usually starts with a thin initial line and is made of the conjunction of a clivis and a pes: this sign may be the one mostly keeping the flexibility of the earlier calligraphic Esztergom notation.

The use of an oriscus is a conservative trait. It is a punctum-variant in the case of voiced consonants. Its rounded shape forming an Arabic 9 is also the remnant of the old Hungarian notation, hence it slowly disappears from the Messine-German-Hungarian Gothic notation of the 15th century.

There is only one ligature as an exception in the archaic notation: in the case of pes subbipunctis of the fragment C.55090 the scribe not only cut the pes into a dot and a line, but also slants the vertical line of dots to the right, similarly to the modern Messine-German-Hungarian mixed notation taking over the calligraphic Esztergom notation, in which the change of the writing direction is one of the big changes compared to the old system. The pes subbipunctis is present on this antiphoner fragment both in its modern and traditional form, this shows the hesitancy of the scribe between old and new solutions and the undeveloped, transient state of the notation.

We can assume that the fragment was written in a peripheral Hungarian scriptorium, based on the musical notation. This is implied by the conservatism of the neume system, by the angular, broken, but conjunct, rustic lines. Some of the traits are typical to Transylvania (e.g. angular pes, hatted climacus, puncta meeting at their side leaning slanted on the lines). Based on them it is likely, that we found the remnants of a codex using the Eastern/Transylvanian type of the Hungarian diocesan notational tradition.

The melody variants of the fragment – supporting the results of the liturgical analysis – show a great correspondence with the Esztergom plainchant tradition. Unfortunately, the only notated choir book preserving the Transylvanian-Várad tradition, the 15th-century Antiphonale Varadinense, which is fragmentary in itself, has a lacuna at the liturgical excerpts documented by fragment F 34, making the melodic comparison impossible. Though our previous observations are supported: the Antiphonale Varadinense’s melodies are significant, individual variants compared to Esztergom. The melodies of the fragment in turn are closely related to the main Hungarian tradition.

Gabriella Gilányi